Amazon has stepped once more unto – and then out of, and then back unto – the breach several times over the last two months, recalibrating with every step. Since early March, we’ve watched a company waging a tense war of image management.

First, in early March, there was the price-gouging. Around the time Amazon told all of its Seattle headquarters employees to work from home (March 4), Amazon shoppers looking to stock up on soap or hand sanitizer or masks found themselves contemplating, for example, a 4-pack of Purell for $345. These products were sold by third-party sellers (the ever-present “bad actors”) and not Amazon, but that loophole doesn’t change the shopper’s reality, and the experience of scrolling through potentially life-saving items priced hundreds of times their actual price was irksome at best (or cold and prickly, as Amazon might say). The issue was widely decried, including by Massachusetts Senator and Amazon critic Ed Markey, and the company worked quickly to restrict this behavior, “blocking” or removing thousands of listings. Still, the problem persisted.

Then, on March 16, amid news of nationwide layoffs and furloughs (and quieter complaints from within Amazon), came the announcement that the company would be “opening 100,000 new full and part-time positions” for delivery drivers and warehouse workers designed “to meet the surge in demand from people relying on Amazon’s service during this stressful time.” As is wont to happen when Amazon puts out a press release, in the following hours, and then days, this blog post was copied and pasted verbatim and widely circulated by countless news organizations. (A Google search for “amazon hiring 100000” yields pages of identical stories repeating the headline and six-digit figure).

Analysis of the announcement, too, was met with a kind of beaming gratitude. It was understood that there were no downsides to this hiring spree. It was simply the market forces doing good, spurring a large and dynamic firm into beneficial action. It was speculated that Bezos would emerge from the pandemic an even more powerful (and newly benevolent?) figure. (The more clear-eyed assessments came from the business press: Forbes, March 17: “Amazon Is Hiring 100,000 Workers: Will This Good News Ultimately Crush Small Businesses?”; The Street, March 20: “6 Ways Amazon’s Hand Is Getting Stronger During The Coronavirus Crisis”; etc.)

In late March we saw articles and opinion pieces parsing the new ethics of online shopping. Understandably, Amazon found itself at the center of this debate. Prompted by Amazon employees speaking out about the insufficient and dangerous conditions they were working in, more pointed questions began to be asked about the safety of Amazon’s warehouses and the treatment of its employees (always a sensitive topic for the firm, even in the best of times). On March 24, Amazon put out another press release outlining the ways it’s “taking care of employees during COVID-19” and citing “150 significant process changes” (though there are nowhere near 150 changes mentioned in the press release). This johnny come lately concern for worker safety is strange given the current cultural climate (let alone the medical/public health climate), but is commensurate with Amazon’s usual attitude towards its workers. By the end of the month, Amazon warehouse employees in New York at least were walking off the job in protest of unsafe working conditions.

In late March we also saw (or more accurately, didn’t see) Bezos decamp to his Texas ranch. Holding court from the ranch, Bezos began to take an apparently more involved role in Amazon’s day-to-day operations. This more active role manifested in daily phone calls with Amazon leadership and other decision-makers, including an Instagram-worthy Zoom call with Washington’s Governor Inslee.

Perhaps less Instagram-worthy was a conference call held April 1, the notes of which were subsequently obtained by (leaked to?) Vice. The main topic of the call – which included Bezos – seemed to be to find a good strategy to deal with New York warehouse worker Christian Smalls, who was fired the previous day, after he organized a walkout at Amazon’s Staten Island warehouse. (Per Smalls, he was fired for the walkout and for wanting to know how many total Amazon employees were sick; per Amazon, he was fired for violating quarantine.)

“He’s not smart, or articulate, and to the extent the press wants to focus on us versus him, we will be in a much stronger PR position than simply explaining for the umpteenth time how we’re trying to protect workers,” wrote Amazon general counsel David Zapolsky. The notes were emailed around Amazon corporate after the call. “We should spend the first part of our response strongly laying out the case for why the organizer’s conduct was immoral, unacceptable, and arguably illegal, in detail, and only then follow with our usual talking points about worker safety. Make him the most interesting part of the story, and if possible make him the face of the entire union/organizing movement.”

(On the same call, “different and bold” ways of donating surplus masks from Amazon’s stockpile were also brainstormed: “It’s a fantastic gift if we donate strategically.”)

I can’t say how successfully Amazon’s “not smart or articulate” narrative was disseminated to the wider world, but the internal emails seemed to have angered other “white-collar” Amazon workers, who maybe felt more solidarity with Smalls than with Bezos et al. In an internal Amazon email chain that circulated, one employee referred to the Smalls firing/Zapolsky email as “probably the most concerning event and subsequent silencing I have seen at Amazon.”

The firing also got the attention of New York Attorney General Letitia James. On March 30, she tweeted “Amazon, this is disgraceful” and that she was “considering all legal options.” Elsewhere, on April 8, OSHA started an investigation at an Amazon warehouse in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, after getting complaints from employees that Amazon wasn’t doing enough to “prevent the spread” of COVID-19.

At the beginning of April, evidently changing tack, Amazon released a commercial titled “Keeping Our Teams Safe”. (There’s also another almost identical cut called “Protecting Our People”; I can’t tell exactly when the ads premiered, but I first saw “Keeping Our Teams Safe” in mid-April, as an autoplay ad on some news site, and both are still airing regularly. Tellingly, neither ad is posted on the Amazon YouTube channel). The commercial is “an ad” in only the coarsest sense. This is damage control bordering on the propagandistic. Over a piano track and casual yet art-directed footage of warehouse employees wearing masks, a woman in a T-shirt that says BE ORIGINAL, stock footage of a Prime jet, and some delivery vans, titles read:

Right now, at Amazon

Nothing is more important than

Safety

Health

Protecting our people

To everyone who makes staying home possible

Thank you

Even without any background knowledge of Amazon’s actions over last several weeks, the spot rings pretty false. With that background knowledge, the dissonance is upsetting.

About this time – April 13 – Amazon put out another press release announcing “hiring for additional 75,000 jobs.” Much shorter, this release says, “Today, we are proud to announce our original 100,000 jobs pledge is filled, and those new employees are working at sites across the U.S. We continue to see increased demand as our teams support their communities, and are going to continue to hire, creating an additional 75,000 jobs to help serve customers during this unprecedented time.”

We will take Amazon at its word that those initial 100,000 positions have been filled. We can even accept the odd and inappropriate civic heroism in their framing of the hirings. But in light of the social distancing rules in place, this line begs at least a logistic question: where are all of these desired 175,000 new hires actually supposed to work? Is Amazon building more facilities? Are they reducing existing employees’ hours to make room for the new ones in spaces that can only be so crowded? “Those new employees are working at sites across the U.S.” seems self-evident.

To be sure, a company vowing to fill 175,000 new positions during unprecedented levels of unemployment is not a bad thing. But it’s also not as meaningful or altruistic a gesture as Amazon would have us believe. Dutifully picked up by the press, but much less enthusiastically than the original 100,000 jobs press release, the announcement was couched in talk of the safety concerns, protests and walkouts Amazon was now facing.

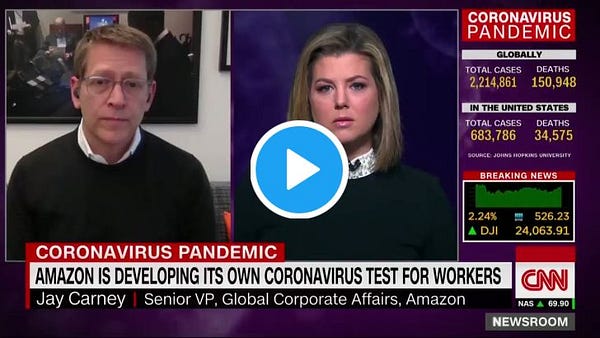

I now come to the final point on the timeline. On April 17, Jay Carney, Amazon’s senior vice president of global corporate affairs did an interview with CNN’s Brianna Keilar. Incredulous, Keilar tries several different times to get Carney to state the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases at Amazon to date.

In a sweater and glasses, Carney never answers the question, saying only, “I don’t have a specific number,” “I don’t have an overall number, it’s pretty imprecise,” and “again, Brianna, I honestly don’t have it.” He runs out the clock with filler words and references to the company’s safety procedures and overtime pay – “which, as you know, is substantial.”

Amazon has always collected data on every customer and, even more controversially, on its warehouse workers. Obviously the number of confirmed cases at Amazon exists. Obviously it is high. Carney’s interview, coupled with the crude “worker safety” ads running during the same time, try to make this reality disappear.

The rambling, dissembling performance is unfortunately reminiscent of Carney’s White House briefings while he was Obama’s press secretary. And Obama, patron saint of technocratic elites (and employer/mentor to a shockingly deep bench of same), was also a specialist at this kind of icy-folksy obfuscation. Carney’s interview reminds me of Obama’s immortal words – spoken to Chuck Todd in a 2014 interview, by way of apologizing for going golfing directly after delivering his statement about the death of James Foley, the journalist killed by ISIS fighters – “I should have anticipated the optics.”

Amazon anticipated the optics. Maybe not every angle, and maybe not always as early as they would have liked. But maybe it doesn’t matter.

Amazon is comfortable with risk. They start narratives and control them tightly until they suddenly don’t (the HQ2 contest for example). But once the facade slips, they get serious without hesitation. They have proven adept at consistently outmaneuvering (or bullying) whoever they need to outmaneuver.

After an arduous two months of battle, we get this from CNN Business: “Amazon has come under fire lately from workers in warehouses concerned about their safety during the Covid-19 pandemic. But this controversy isn’t making investors nervous. Not at all.” Today, Amazon is victorious, heralded as “the ultimate coronavirus-proof stock.”

“One thing we’ve learned from the COVID-19 crisis is how important Amazon has become to our customers,” reads the first line of Bezos’s 2020 letter to shareholders, published on April 16. We’ve also learned some other things, but I’m afraid it’s too late for that.

Live Bait 🐟

Netflix borrowed another billion dollars to make shows.

Reckitt Benckiser released a statement on the “improper use of disinfectants.”

Joe Biden has a podcast, and he’s really into it.

China arrested five Huawei employees for talking about the company’s sales in Iran on WeChat.

A University of Chicago study found that “Greater exposure to Hannity relative to Tucker Carlson Tonight leads to a greater number of COVID-19 cases and deaths.”

Johnson & Johnson debuted a weekly live show about developing a COVID-19 vaccine.

Facebook invested $5.7 billion in Reliance Jio, the biggest telecom in India.

A court ruled that Call of Duty is art.