On Monday, Ben Smith’s media column in The New York Times was about Condé Nast. It was somewhat remarkably headlined “Anna Wintour Made Condé Nast the Embodiment of Boomer Excess. Can It Change to Meet This Crisis?”

It’s safe to say Smith assumes Betteridge’s law of headlines applies to that second sentence. But he’s obviously more interested in the first part, going out of his way to highlight the many ways in which Condé Nast and Anna Wintour, its figurehead, are the “embodiment of boomer excess.”

What this means is really anyone’s guess. But to paraphrase Bill Clinton – a boomer par excellence – it depends on what your definition of “boomer excess” is. Here, it mostly amounts to a variety of vague “suffer for fashion”-style references: Wintour’s “regal presence” in the first row; other Vogue editors, nervous about the coronavirus, who wouldn’t “dare” ask to go home; Wintour making “arch jokes” about people who “fled” Milan; talk of “theatrical flourishes and lavish lifestyles;” a reference to a designer referring to Wintour as “santanic” on Instagram; Wintour’s slowness “to adjust to changing cultural norms” and knack for still doing out of touch things like “calling people fat” and “wearing fur;” the line “Nobody is putting on a Givenchy cape anytime soon.”

The Zoolander/Devil Wears Prada flavor present in all of this is pretty lame. But the message is clear: Condé Nast is guilty of frivolity, an offense deemed worthy of scorn by The New York Times. Look at it – poor stupid slow Condé Nast, still out there in its little Givenchy cape as “the crisis is set to sweep aside the vestiges of a more luxuriant media age.”

On the Times website, someone named Deirdre commented on the piece: “Sounds like the author, Ben Smith has a huge ax to grind, not sure why?” I couldn’t have put it better myself. But I’m afraid this axe-grinding is not an isolated incident.

Smith’s was not the first Times piece in the past month to report on Condé Nast’s management struggles during the pandemic. On April 13, the paper published an article first bringing Condé Nast’s “lavishness” to our attention (the company is described in the first line as “the most glittering of all magazine publishers,” and some version of the word “glossy” appears four times).

The piece (not by Smith) is about the news that Wintour, Condé Nast CEO Roger Lynch, and other employees “earning $100,000 or more” will all take salary cuts starting in May, and that layoffs are under consideration. We also learn, confusingly, that Condé Nast is not “directly asking for government money,” but is “exploring the use of relief programs and stimulus packages in certain regions.” Then the authors weigh in on things that, frankly, are outside the purview of a “news article”:

Requesting government assistance would be an unusual move for a company whose high-paid editors have enjoyed perks such as town cars and clothing allowances. It could also risk alienating readers, for whom the idea of a glossy magazine publisher requesting funds for certain employees may be anathema.

Besides the holier-than-thou tone – “unusual move” is dripping with condescension, and heaven forbid someone ride in a town car! – it’s pure speculation, free of sources and quotations.

The dramatic framing in both of these recent pieces – glamorous media moguls out of step with pandemic – is weird. I also find it strange that the Times is going to such lengths to criticize (or, report on) a fellow publishing company for its suffering during a global pandemic that the newspaper itself has said will touch every aspect of our lives – and has, in fact, caused virtually every other media/publishing company from McClatchy to Vox to reduce its staff.

(The Times, of course, has also suffered lay-offs in the past. Most recently, staff has been reduced, on and off, since about 2008. In 2017, the paper eliminated all copy editor positions, and walk-offs ensued. Fortunately, so far, it seems the Times has not laid anyone off during the pandemic.)

Moving backwards a couple more days, on April 9 the Times published yet another piece about the magazine industry, titled, bluntly, “What’s the Point of a Fashion Magazine Now?”

Within, we get things like this:

Fashion magazines are vehicles for luxury fantasies. They sell readers on consumerist dreams, sandwiching glossy images of supermodels and stars between advertisements for $50,000 watches and $250 moisturizers.

Oh, okay! Now I know! And in case you may start to think that the magazine industry’s current woes are simply the result of the logistical challenges posed by the pandemic putting all those lavish photoshoots on hold, think again:

It’s that magazines were already a fraught business. It’s that many people have been re-evaluating their moral relationship with consumption. It’s that resentment and even rage has risen toward celebrities and other elites – a pampered pool of cultural figureheads who fill the pages of contemporary fashion publications.

Where is this stuff coming from? Seriously? While some of the claims above are no doubt “fact-based,” the impression is overwhelmingly one of facile speculation, snide judgment, and self-satisfaction. Apparently, the moral high ground, in all cases, belongs to The New York Times and they will defend their territory when necessary. This is the “voice-of-God” – that platonic ideal of journalism – taken to its extreme.

This constant above-it-all point of view is hard to take. Mistaking aloofness for objectivity, too often the Times’s editorial voice borders on petty, with hints of schadenfreude, glee, or indignation here and there. Usually, every story could end with “We told you so.”

But this defensiveness is understandable, in a way. Lest we forget, The New York Times is a publishing company, not an ethereal all-knowing orb that has existed since time immemorial, floating above all of us. No, it’s a publicly traded corporation, with a mandate to serve its shareholders and inform – and sell to – its specific readership. It’s a brand, with a vested interest in protecting itself from others who might try to harm it.

Seen in this light, “editorial voice” can easily become “brand voice.” And every decision the Times makes becomes, fundamentally, a marketing decision. (It’s also not helpful that I keep reflexively using “the Times,” as if it were a single living entity; it’s people who decide what appears in the newspaper.)

By painting Condé Nast repeatedly with the “lavish” and “glossy” brush, the Times is implicitly burnishing its own brand, even subconsciously. Reading pieces like these, the reader comes away with not only a negative impression of Condé Nast – a competitor – but with a positive impression of The New York Times as well. Through the mist of glamour, frivolity, and excess, the Times stands out as frugal, level-headed, solid, responsible, trustworthy.

These are all good words to associate with any newspaper brand; they are all words The New York Times wants associated with its newspaper brand. Over and over, we are meant to connect The New York Times with these words. Moral superiority is a brand position.

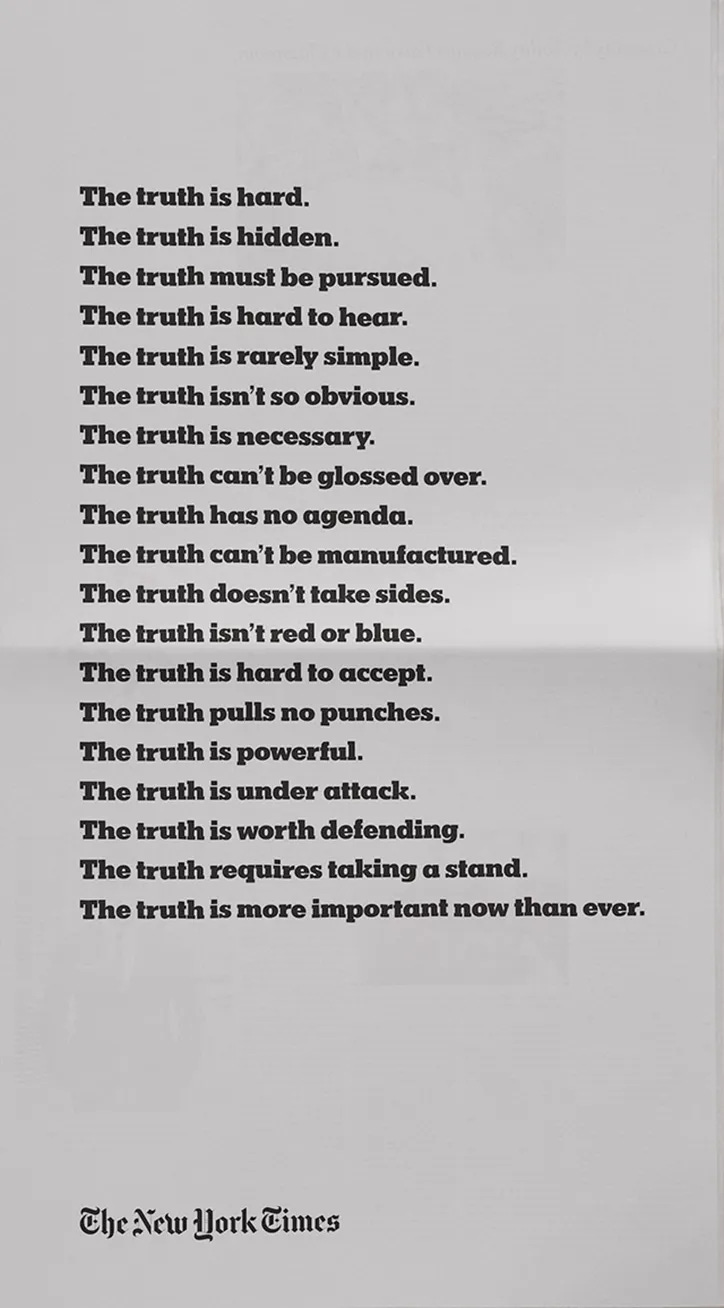

The emphasis on difficulty, on never taking the easy road, on dedication, on stubbornness, and above all on “the truth”, while maybe always a part of the Times’s “DNA,” comes to us in its clearest form courtesy of an ad campaign devised by Droga5 and launched in 2017.

This was the first ad campaign the Times had run in over ten years, and it worked wonders. Per Droga’s case study:

The campaign not only lifted public opinion of The New York Times but helped drive conversion as well, acquiring more subscribers in just 24 hours than the Times had in the six weeks prior to launch.

The first quarter of 2017 became the Times’s best quarter ever for subscriber growth, and in the second quarter, the paper passed 2 million digital-only subscribers, a first for any news organization.

The truth, then, is lucrative. It’s own-able, and sellable. The truth also doesn’t exist. But now it belongs to The New York Times, and it’s worth defending.

To close, I want return to Ben Smith for a moment. Smith, who was the founding editor in chief of BuzzFeed News, where he spent the last eight years, started as “the media columnist” at The New York Times on March 1. Smith’s debut media column was also ostentatiously provocatively titled: “Why the Success of The New York Times May Be Bad News for Journalism.” Subhead: “In his debut, our new media columnist says The Times has become like Facebook or Google – a digital behemoth crowding out the competition.”

The piece made waves among media types and was heavily discussed and shared – and gently mocked for its faux baiting headline, smugness, and the meta nerdiness of criticizing-idolizing your new employer on your first day. But the column’s all-over-the-place self-aggrandizing doesn’t let up. I’ll quote more or less at random, and at length:

The Times so dominates the news business that it has absorbed many of the people who once threatened it

That was back in the heady days of digital media in 2014, and I was at BuzzFeed News, one of a handful of start-ups preparing to sweep aside dying legacy outlets like The Times.

The gulf between The Times and the rest of the industry is vast and keeps growing: The company now has more digital subscribers than The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and the 250 local Gannett papers combined

He believes The Times is not dominating the market so much as creating one.

The deal, along with The Daily, the popular weekday podcast at The Times, could form the basis for an ambitious new paid product — like the company’s Cooking and Crossword apps — that executives believe could become the HBO of podcasts.

Because The Times now overshadows so much of the industry, the cultural and ideological battles that used to break out between news organizations — like whether to say that President Trump lied — now play out inside The Times.

The rise of The Times from wounded giant to reigning colossus has been as breathtaking as that of any start-up.

Times executives say they are also looking for a way to help out their weaker cousins

Just a few years later, amid a deepening crisis in American journalism, and a sustained attack from the president of the United States, Times stock has rebounded to nearly triple what it was in 2014 and the newsroom has added 400 employees. The starting salary for most reporters is $104,600.

And The Times has swallowed so much of what was once called new media that the paper can read as an uneasy competition of dueling traditions: The Style section is a more polished Gawker, while the opinion pages reflect the best and worst of The Atlantic’s provocations. The magazine publishes bold arguments about race and American history, and the campaign coverage channels Politico’s scoopy aggression.

The paper is now quietly shopping for dominance in an adjacent industry: audio.

“There’s no new thing coming. And the editor of BuzzFeed News, who was probably the chief insurgent, is now writing this column for you at The New York Times.”

I guess the conceit of the piece is double-edged self-reflection, plus a kind of (again, defensive) ironic self-deprecation. Or maybe it’s not? Anyway, it’s impossible to not feel the real, uncut self-satisfaction in almost every single line. (Referring to yourself, via someone else’s quote, as “chief insurgent” is really something else.)

Smith concludes his debut Times column with this raison d’etre: “My job as columnist here will be an exciting and uncomfortable one – covering this new media age from inside one of its titans (though I hope you’ll tell me if I ever get too far inside).”

But as media critics named Ben go, Smith is no Bagdikian. I think he was already way “too far inside” before he even started.

Through it all – and there are new examples published almost every day – The New York Times’s sense of self-regard remains disturbing to me. It’s become overwhelming, oozing into almost everything the company produces, and making it bad – or at least much worse than it should be, and much more dangerous. The Times editors and writers responsible are either unwilling or unable to rein it in. Or, they’re unaware of it. (It’s not clear which of these three scenarios is the scariest.) I guess a job at the Times does wonders for your self-esteem.

This description of The Daily host Michael Barbaro (from a bone-chilling New York magazine profile) can probably apply to the entire newspaper: “highly regarded by himself and others.” Yes, people like The New York Times. But not as much as it likes itself.

But, you know, as Deirdre would say, it sounds like the author has a huge axe to grind, not sure why?

Live Bait 🐠

Kara Swisher is leaving “Recode Decode” to start a new podcast with The New York Times this fall…

…This comes a week or so after the announcement that Swisher’s other podcast, “Pivot,” is “joining” New York magazine, where she will also become editor-at-large (?).

Sean Hannity sent a 12-page request for apology/threat to sue to The New York Times because of opinion columns (including one written by Swisher, who is also a Times contributor) and news stories that he says mischaracterized his coverage of the pandemic. A Times lawyer replied “‘no.’”

“The Malaysian Job”: Andrew Cockburn on global financial fraud and the complicity of Wall Street and Washington.

Discovery, TLC, Food Network, and HGTV are doing pretty well.

A “top-secret” Michelle Obama documentary is coming to Netflix on May 6.

“23 Hours to Kill” is Jerry Seinfeld’s first “original comedy special” in 22 years; it’s coming out on Netflix on May 5.

“At least 20 coronavirus-related documentary projects” are in the pipeline.

A Wall Street Journal report found evidence contradicting Amazon’s previous messaging about its use of third-party seller data – including claims made by an Amazon executive in sworn testimony last year; in light of the report, the House Judiciary Committee says the company may have misled Congress.

French courts rule Amazon must stop selling nonessential items in France to protect workers.

Today, May 1, frontline employees at Amazon, Target, Instacart, and more, will walk off the job.