There is one image of Richard Nixon that appears over and over and over again. The ubiquitous image comes from within his own camp, reproduced often by his family and by his estate. It appears in countless biographies, in portraits ranging from sympathetic to critical. And it can also be found in the most strident of anti-Nixon portrayals.

It is not the jowly Nixon, with both arms awkwardly raised, index and middle fingers parted in an oddly hollow approximation of peace signs – more a finger position than a political statement. It is not Tricky Dick, it is not Richard “I am not a crook” Nixon. In the introduction to her 2007 biography, Richard M. Nixon, Elizabeth Drew writes, “Nixon was much more than the cartoon figure with the perpetual five o’clock shadow, his arms extended upward, his fingers forming a V.” Indeed, Nixon was and remains more than that. He was a deeply fascinating figure, inspiring morbid curiosity, obsession, devotion, and revulsion.

The political cartoon version of Nixon is a classic, lasting image. But it is obvious, a clear anti-Nixon symbol. There is another image that is perhaps even more lasting, more common, and more perplexing. And all the more powerful – and certainly more surprising – for its nonpartisan nature.

The image is this: Richard Nixon sitting in the Lincoln Sitting Room, upstairs at the White House, with a fire burning in the fireplace and the air conditioning on high.

At first, it seems like a throwaway description of a somewhat odd habit. But this surprisingly virulent image, once you begin to notice it, makes an appearance in almost every single account of Richard Nixon produced in the last six decades, from the anecdotal to the magisterial. Through repetition, the image begins to take the shape of myth, in Roland Barthes’s sense of the term (“myth is a system of communication… it is a message”). The fireplace/air conditioning image means to tell us something – it has, it had, a purpose – but what? And where did it come from?

The image of Nixon sitting in the Lincoln Sitting Room, fireplace burning while the air conditioner blasts cold air seems to be variously attributed to First Lady Pat Nixon and the younger Nixon daughter, Julie Nixon Eisenhower. But its earliest, widest instance of dissemination dates, most likely, to May 26, 1970, when older daughter Tricia Nixon gave a 24-minute tour of the White House on CBS’s 60 Minutes. In the segment – which is titled “Upstairs at the White House with Tricia Nixon,” and clearly recalls Jackie Kennedy’s famous 1962 televised White House tour – 60 Minutes hosts Mike Wallace and Harry Reasoner follow Tricia as she shows them around the Nixon White House. Throughout, Reasoner and Wallace ask her questions about the interior decoration and other various objects (“Who chooses the books? Are these all your mother and father’s books, or?”, “There’s a card table over there in the corner, too, who does that?”, “What’s that paper weight over there, on top of that manila folder?”, “Is that a desk or a buffet over there?”, “What about the china, Tricia?”, “Does your father have a snack in here too?”, etc.). The rapport is good, the banter witty.

In the White House dining room, about 15 minutes into the tour, Harry Reasoner mentions the fireplace – “You could have a fire while you’re eating, if you want” – and Tricia remarks,

Yes. We do have a fire, almost every night that we have dinner here. And my father absolutely loves to have a fire. In the summer and the spring when it’s really warm out and you wouldn’t think of having a fire, he’ll turn the air conditioning up just so we can burn one.

Then, in what was then to-date perhaps the most detailed and most widely-viewed mention of the image in question, Reasoner adds, a little reverently,

Your mother once said that he liked to go up to his study, light the fire, turn up the air conditioning to maximum so it’ll be bearable, put on some music by Mantovani and look up at the Washington Monument.”

Tricia, maybe surprised at his level of detail, replies, “That’s right. He does that.”

I have been unable to locate an interview with Pat Nixon that contains the fireplace/AC detail in its initial original form. But in Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything, Salvatore Basile recounts an instance in 1969 when Pat Nixon showed a reporter her husband’s new White House “hideaway” (presumably the Lincoln Sitting Room), quoting the First Lady saying, “He has a fire in here every night and plays classical music on the phonograph. We always have a fire, even in summer. Air conditioning, you know.”

I can’t find a more specific mention of Pat discussing her husband’s fireplace habit, with the Mantovani and the Monument details, as referenced in Reasoner’s “Your mother once said…” comment. It’s possible Reasoner is referring to the above quote, taking “classical music” and embellishing it specifically into “Mantovani.” Or perhaps Pat Nixon’s remark is somehow apocryphal. But Nixon’s general behavior is real, and Reasoner got the anecdote from somewhere – even if he embellished a bit – and felt compelled to share it on 60 Minutes.

And what about Julie Nixon Eisenhower spreading the word? In Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1990 biography Nixon Volume II: The Triumph of a Politician 1962-1972, the original description of the fireplace/AC image is attributed to Nixon’s younger daughter, Julie. Ambrose describes how Julie worked as a volunteer White House tour guide in the summer of 1969 (a year before the 60 Minutes tour) and gave private tours of the second floor to lucky tourists she’d pick at random from the public tour groups: “In the Lincoln Sitting Room, her father’s favorite, she would reveal that even on the hottest summer days he liked to turn on the air-conditioning full blast, then have a fire in the fireplace.”

No matter who “said it first,” it seems clear that Nixon’s wife and daughters began spreading this somewhat personal, anecdotal image of the president in the Lincoln Sitting Room with a fire blazing and the air conditioning blasting.

The day after Tricia’s 60 Minutes episode aired (May 27, 1970), The New York Times ran a review of it, calling Tricia a “charming, lively and poised” hostess, who navigated the segment with “spontaneous vivacity and humor.” And the Times piece contained a couple of references to the fireplace/AC image, too:

Miss Nixon related how, in preparing his speech of Nov. 3, her father had a sudden idea at 2 A.M. and lit the fire in the fireplace. “He sent the White House Fire Department into an absolute panic,” Miss Nixon recalled with a laugh. “And they arrived here en masse, about 2:30 A.M., to find just a fire burning and my father working on a speech.”

Even stranger, the Times mentions how Tricia “also confirmed anew her father’s penchant for open fires, even if it means turning up the air-conditioning full blast.”

“Confirmed anew” suggests that, apparently as early as 1970, Nixon’s “penchant for open fires” was already very well known. (The Times piece may also include the first mention of “full blast” – a common description, as you’ll soon see.) This “penchant” is interesting. By 1970, Nixon had been a public political figure for two decades, but only president for about a year – and the different fireplace/AC retellings seem to be contained to the Lincoln Sitting Room, suggesting a presidential habit. And it’s unlikely he would have been curling up by the fire upstairs in the White House when he was Eisenhower’s vice president.

I can’t say specifically about open fires, however, it seems there was a media/public fascination with Nixon’s response to temperature well before 1970. In Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything, Basile describes the 1960 presidential race between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy and the famous first-ever televised presidential debates. He writes:

The debates themselves were enlivened by reports of the candidates’ clashing opinions about the most pleasant temperature for debating. Their reactions to the hot lights were very different, a fact that showed plainly during their first encounter; Kennedy appeared comfortably relaxed, while viewers saw a copiously perspiring Nixon, mopping off in view of television cameras when he thought no one noticed.

At the second debate a week later the studio was a cool 64 degrees. Nixon seemed to like the temperature, but Kennedy did not. He sent an aide

to the basement to find a Nixon aide standing guard over a dialed-down thermostat, which resulted in the Kennedy aide’s threatening to bring in the police. The Nixon aide retreated, and by air time the temperature had climbed back up to 70 degrees.

Nixon’s idiosyncratic temperature preferences, then, seem to have been common knowledge. Another Times piece, from 1972, about the behind-the-scenes machinations of a Nixon television interview on CBS, also mentions his fireplace fixation, reporting that in addition to lighter pancake makeup and other pre-show suggestions, the CBS producers

dissuaded White House aides from igniting Mr. Nixon’s woodburning fireplace. The Mimi people are very big on woodburning fireplaces (it is a rare aide who does not have one lit during the winter), but this time they swallowed their preferences in the interests of dryness.

Moving away from contemporaneous news reports and into the historical/biographical record, we find, over the decades, the fireplace/air conditioning image to be even more common, even more codified, and even more mythologized.

In her 1984 autobiography, First Lady From Plains, First Lady Rosalynn Carter writes of arriving in the White House in the late 1970s:

We were surrounded by history, evoking both recent and past memories of American presidencies. We explored the Lincoln Bedroom and the Queen’s Bedroom, on the east end of the sitting hall, and found Nixon’s favorite room, the Lincoln Sitting Room, which adjoins the Lincoln Bedroom. It’s a small, cozy room with a corner fireplace, and Julie Nixon Eisenhower once said that her father liked a fire so much that he would build one here even in warm weather and turn on the air conditioning.

In his 1989 autobiography, Did They Mention the Music?, composer Henry Mancini (The Pink Panther theme, et al.) describes an evening he and his wife Ginny spent at the Nixon White House in 1969:

Like so many people who dined at the White House during the Nixon administration, we noticed on this June day the president’s peculiar practice of keeping a roaring fire in the fireplace and the air-conditioning going full blast.

Mancini also repeats the classical music detail, mentioning Mantovani and adding another oft-repeated detail to the fireplace tableau – the Victory at Sea soundtrack. After playing the piano at Nixon’s request, Mancini asked Nixon what his favorite album was, and Nixon pulled the Victory at Sea soundtrack off the shelf. Mancini writes,

He said, “I sit here by the hour and listen to that album.” He had several Lawrence Welk albums, some Mantovani, and The Sound of Music, along with some Tchaikovsky.

In Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1990 biography Nixon Volume II: The Triumph of a Politician 1962-1972, the fireplace/AC image is mentioned in a passage, already quoted above, about Julie Nixon Eisenhower working as White House tour guide:

In the Lincoln Sitting Room, her father’s favorite, she would reveal that even on the hottest summer days he liked to turn on the air-conditioning full blast, then have a fire in the fireplace.

In his 2001 biography, President Nixon: Alone In the White House, Richard Reeves writes,

On September 8, sitting alone in front of the burning fireplace – with the air conditioning on full blast – in his EOB [Executive Office Building] hideaway office, Nixon had filled a legal-size page with political thoughts…

In Conrad Black’s 2007 biography Richard M. Nixon: A Life In Full, there’s this concise mention: “Because he liked active fireplaces, he sometimes had the fire lit in the stifling heat of Washington summer and balanced it by turning up the air conditioner.”

In John Coyne and Linda Bridges’s 2007 biography of William F. Buckley, Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement, during a section about Jimmy Carter, we find this parenthetical description:

There was President Carter sitting in front of a White House fireplace (calling up for some of us memories of Richard Nixon, who liked blazing fires with the air conditioning turned up full blast), wearing a too-large old cardigan and giving his “malaise” speech.

In Elizabeth Drew’s 2007 biography Richard M. Nixon, part of the The American Presidents series, we get:

Most evenings when Nixon was in Washington, he sat alone in the Lincoln Sitting Room in the White House residence, air-conditioning on high, a fire blazing in the fireplace, listening to the sound track of the television documentary Victory at Sea.

And, most recently, John A. Farrell’s massive 2017 biography Richard Nixon: The Life contains:

The problems of the first weeks in office were trifles: they could not get the White House fireplaces to draw (Nixon liked a crackling fire – even in warm weather, when he would compensate by turning on the air-conditioning), nor the president’s new dog, an Irish setter named King Timahoe, to lie at Nixon’s side.

Elsewhere, Farrell goes further, including other mentions of fireplaces that played a prominent roles in Nixon’s life, writing:

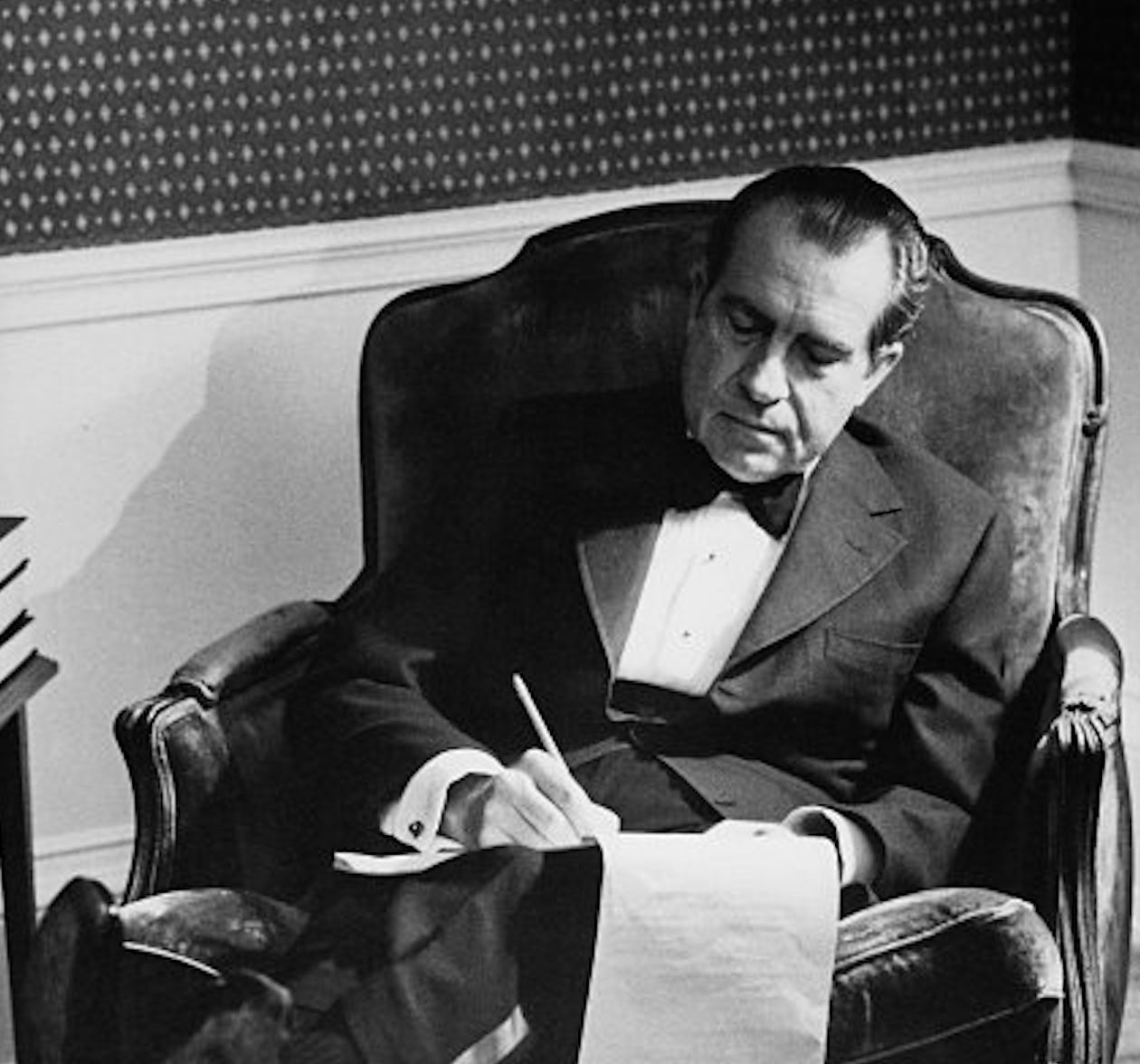

In the evenings, Nixon would nestle in his armchair by a fireplace, prop his feet on a hassock, and cover his yellow foolscap with admonitions… For background Nixon would play stirring romantic music on the stereo – Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Rachmaninoff concertos, or that old favorite the score from Victory at Sea.

Farrell also quotes from a letter Nixon wrote to H. R. Haldeman, his chief of staff, in which he gives some very specific fireplace-centric interior design instructions:

When the oval room is re-done I would like to have the coffee table in front of the fireplace replaced by one that does not block the view of the fireplace from the desk.

And a fireplace even features prominently in Farrell’s account of an earlier pivotal moment in Nixon and Pat’s romantic-political life, when Nixon promised her he would not run for public office again. Farrell writes, “Early in 1954, as they sat before the fireplace in their Tilden Street home, Dick promised he would not run again.”

After biographies, the fireplace/air conditioner image can be found in the fictional world as well. In Ann Beattie’s 2011 novel Mrs. Nixon, a novelistic “imagining” of the First Lady’s life, Beattie begins a chapter with a meditation on the fireplace:

Mr. Nixon likes a fire in the fireplace, even during summer, when he would have a fire lit and turn on the air-conditioning. He wanted a fire at Camp David, the White House, San Clemente – and also at Julie Nixon and David Eisenhower’s, those times the Nixons brought dinner from the White House Kitchen. RN, himself, is said to have lit the fire.

And the image even appears in the movies. It’s spoken of by a fictionalized Nixon himself, in Robert Altman’s 1984 film Secret Honor, written by Donald Freed and Arnold M. Stone and based on their stage play of the same name, which debuted in 1983. Secret Honor – subtitled “A Political Myth” – is a 90-minute monologue by Philip Baker Hall as a late 1970s Richard Nixon, alone and contemplative in his heavily secured New Jersey home, pacing his study and recounting his life, defending himself into a tape recorder, taking notes in his yellow legal pad, brandishing a revolver, and laughing and crying at his mistakes. At one point his thoughts seize on his time in the White House:

How I used to love being president. I used to enjoy that so much. I cannot tell you how much – I used to sit in the Lincoln study, with the fireplace going, the air conditioning on. I used to love to sit in there and think about Lincoln, Washington. What a liar he was, that fuckin’ Washington.

And Nixon, Oliver Stone’s much more widely-seen 1995 film, contains, as far as I know, the only filmed visualization of the fireplace/AC detail. In fact, the image opens the film. The first post-credits scene begins in a dimly-lit Lincoln Sitting Room as Alexander Haig enters to find Richard Nixon (Anthony Hopkins) sitting by a roaring fireplace. Haig hands him a couple of tapes. Haig looks down and notices air coming from the air conditioner vent: there is an insert shot of the grate, with a frayed ribbon tied to it, blowing to show that air is flowing. The image, actually, doesn’t translate as well to film; it remains better in words. But its prominence in Stone’s film – the first time we see Richard Nixon in this 3-hour, Oscar-nominated biopic, we also see the fireplace with the air conditioning on – is telling.

Moving past biographies, autobiographies, novels, and films, the fireplace/air-conditioning image appears in official records as well. It can be found in articles published by the Richard Nixon Foundation (in a 2009 post, the detail is invoked defensively to jab Obama, who during his first full day in the White House was photographed without his suit jacket on, after having “cranked up the thermostat”) and the White House Historical Association (which was founded by First Lady Jackie Kennedy in 1961).

Finally, the image is officially commemorated in the Richard Nixon Library & Museum in Yorba Linda, California. According to a 1990 Washington Post piece about the grand opening, the Museum features “a mock-up of the Lincoln Sitting Room, rather than the Oval Office, so popular in other presidential libraries.” The Sitting Room mock-up is included, of course, because “Nixon did most of his speech-writing there, with the air conditioning up high and a fire in the fireplace.” And, the Post notes in an aside, “The National Archives, which has some say over safety conditions in buildings that borrow state gifts for display, has raised some questions about the gas-fed fire.”

In all of these depictions, the initial essence of the fireplace/air conditioning image is related, then often added to, with other surprisingly consistent embellishments. The Lincoln Sitting Room is always Nixon’s “favorite room.” And he’s always sitting “on his favorite chair,” which was, Tricia says on 60 Minutes, taken from the Nixon apartment in New York City; this “favorite chair from the New York apartment” makes the rounds in the biographies.

Nixon is always writing on a yellow legal pad. In Tricia Nixon’s words, it’s her father’s “trusty yellow pad.” The legal pad also makes an appearance in Drew, who writes, “He spent a great deal of his time writing notes to himself on a yellow legal pad.” Farrell mentions Nixon writing in a “yellow foolscap.” In Secret Honor, we see Nixon writing on a long yellow legal pad. And the president’s affinity for the Victory at Sea soundtrack, “that old favorite,” as Farrell described it, is also a surprisingly common detail.

Nixon’s eating habits merit several mentions in the biographies as well. Black writes:

His breakfasts (juice, plain cereal, unbuttered toast, and coffee) and lunches (a pineapple ring with cottage cheese flown in from Knudsen’s Dairy in Los Angeles) were taken alone and rarely last more than ten minutes.

A 2015 piece in America magazine mirrors this, though with the more extreme detail that his “everyday lunch” was, in fact, “a scoop of cottage cheese with a slice of Bermuda onion, lathered with ketchup or Worcestershire sauce.”

So what is to be made of all this? The facts and the tics and the details add up in any account of Richard Nixon: the fireplace with the air-conditioning on “full blast,” the yellow legal pad, the cottage cheese with ketchup, Victory at Sea, always “alone.” Are these details meant as put-downs? Or were they initially designed to purposefully paint Nixon as a middle-brow everyman – an attempt at relatability that got out of hand? In his diaries, published in 1994, H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, writes often of efforts by Nixon’s staff to “establish the mystique of the Presidency.”

Though repeated again and again, over the years – in these passages and others like them, and in books, films, articles, and interviews – the desired meaning of the fireplace/air conditioning image is still not obvious. Barthes wrote, “I don’t know whether I agree with the old proverb that repeated things give pleasure, but I do know that at least they signify.” But what’s so strange about this particular “repeated thing” is that what it signifies is so unclear, so un-owned, so not-universal. The image of Nixon sitting by the fireplace with the air conditioning on high is powerful myth-making, repeated over and over. Yet it remains unclear what the meaning of the myth is supposed to be – which is unusual.

What is it we – and all the chroniclers – seem to like so much about this fireplace/air-conditioning thing? Why has it come to be one of the most lasting, defining images of President Richard M. Nixon? What is it we’re trying to say about the man with this image? What does it mean? What was its intended meaning – and how did that intended meaning change over the decades?

Is it about the physical juxtaposition of old-time American politics, humble FDR Fireside Chat coziness crossed with modern man’s destructive technology-driven consumption habits? Is it the ultimate postmodern act? Is it a metaphor for an obsession with control – and how futile and Sisyphean control always is? Is it an illustration of Nixon’s naive hubris? Is it about man vs. nature? The natural world vs. Western technological prowess? Or Nixon vs. everyone else? Is it an illustration of, to borrow the title of another Nixon biography, the arrogance of power? Is it a repulsively hedonistic habit that opens up Nixon’s psyche just a little bit more? Or is it something else? Is it an illustration of a great man deep in thought, forming policy, deciding fates? Is it a portrait of a man in respite, grabbing a minute of thoughtful calm after a long day of leading the nation? Or is it none of that? Is it just a simple pleasure of a busy man? A folksy quirk? Is it relatable? Enviable? Laughable? Historical? Epic? Or is it just a detail, for detail’s sake? Is it a little story that started innocently and grew and grew until it was able to take on any meaning one would like to attach to it? Or is it even less than that? Is it just a little weird, something memorable enough to include in a report and then forget about? Is it merely texture? Just “good copy,” as a reporter might’ve said back then?

It is more powerful than – because it is more personal than – the image of Nixon leaving the White House and boarding Marine One post-resignation. It is maybe more powerful than any other piece of Nixon-era photojournalism. There is no photo of this fireplace/AC image. In fact, it physically cannot be photographed. The only visualization I know of – in Stone’s Nixon – isn’t even a complete picture, because it only makes sense cut together with insert shots. And even then, the cold blowing air is invisible – and anyway we can’t feel the temperature clash on film. The image – the anecdote – is powerful because it describes a physical sensation that is almost pleasurable, a feeling of illicit cold and cozy warmth. It evokes a sense of peace and quiet, under control.

In practice, though, the image is surely more unflattering than it is enticing. Which is why its wide, initial dissemination from within Nixon’s own campaign, and by his own family – Pat, Julie, Tricia – is so bizarre. It’s an odd choice for an official anecdote. At best, it seems to paint President Nixon as a folksy man of odd indulgence, yet one who is nevertheless out of step with the times – and with his own policies.

Nixon himself founded the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. The EPA began its life strongly advocating for energy conservation, and air conditioners, as Basile notes in Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything, were the first appliances to be scrutinized by the Agency. In 1973, Nixon announced conservation measures, including, per Basile, “a reduction in the level of air conditioning in all Federal office buildings throughout the summer.” He also recommended that, to conserve energy, American homeowners should use their air conditioners more sparingly, and run them at less-cold temperatures. The self-inflicted hypocrisy was obvious. Considering, as Basile writes, “Nixon’s own extensively publicized habit of air-conditioned roaring fires, that particular recommendation drew little more than jeers from the public.”

So then what, finally, are we to make of the image, if, in his own day he was being criticized and laughed at for his fireplace/air conditioning “habit”? Nixon was a man of odd tics – or at least a man whose odd tics were (and are) recounted more often than others’. He is perhaps the first American President who fascinated the country because of everything he did wrong.

Maybe the fireplace/air conditioning image was seized on in the early good days and planted in the public’s mind to temper and humanize Nixon’s public persona as a somewhat remote-seeming figure – something like tentative mythologizing? If Nixon’s legacy had become that of a more successful and less reviled politician, the fireplace/AC image, along with his other quirks, would today be inherently framed as endearing, the eccentricities of a powerful, effective, beloved man. As it is, there is a sense of pity to the image that is impossible to escape, even when its’s used in service of hagiography. In the warmest light, the image is still a contradiction, at best: unflattering yet interesting, revealing a kind of determined yet misunderstood oddball.

Obviously there are parallels to be drawn (and have been drawn, often) between our current president and Richard Nixon. There are the more obvious similarities, like the impeachment, the hatred of – and attacks on – the media, the paranoia, the lists of enemies, the overt racism.

But there are other similarities that also seem worthy of scrutiny. These often manifest themselves in images, rather than in policies or historical events, and are less remarked-upon. There is, for example, the self-consciousness of both men (especially in terms of their worry over their representations in the media), the unpleasant eating habits, and the loneliness. They both share extreme obsessions with Abraham Lincoln (Nixon’s “favorite room” was the Lincoln Sitting Room; Trump twisted arms to conduct a Fox News interview inside the Lincoln Memorial, etc.). And surely there is some heavy parallel to be drawn between Nixon’s obsession with committing his every conversation and thought to audio tape and Trump’s obsession with doing the same via Twitter.

(Another piece of lore has it that Nixon was spectacularly bad at understanding and using mechanical devices, an inability that both helped and hindered him once his White House tapes became public knowledge. Trump’s general incompetence is also a widely-known quirk.)

In the end, after all has been said and done, on the surface, Nixon mostly comes across as a hapless paranoiac verging on a villainous square. Oliver Stone said in 1995 that he by no means sees his film as the definitive statement on Nixon, but as “a basis to start reading, to start investigating on your own.” In certain respects, Nixon was a good politician, and also a uniquely complicated person. He was bad, but not only. His complexity inspires justified fascination, and deep research.

Today, the difference is that Trump’s personal “complexity” is only gratuitous, and unsatisfying. Trump is undeserving of emotional scrutiny: we probably do not need 3-hour biopics and 40 different dictionary-sized biographies about Donald Trump. But we will get them anyway, so it’s worth wondering now what the lasting image(s) of Trump’s presidency will be. What will the media deem important? What will the official chroniclers gravitate towards? What will they make stick?

In the 1957 preface to Mythologies, Roland Barthes writes of

a feeling of impatience with the “naturalness” which common sense, the press, and the arts continually invoke to dress up a reality which, though the one we live in, is nonetheless quite historical: in a word, I resented seeing Nature and History repeatedly confused in the description of our reality, and I wanted to expose in the decorative display of what-goes-without-saying the ideological abuse I believed was hidden there.

Images are the tools the media uses to create meaning. And we can’t say which image, years after the fact, Trump’s time in office will be distilled into. It’s important to try to remember today as it is, and to keep track of the reality of this moment. It will matter.

Live Bait 🐙

Kim Kardashian West has signed an exclusive podcast deal with Spotify; there aren’t many details yet, but the podcast will be about criminal justice reform, wrongful convictions, and Kardashian West’s work with the Innocence Project.

Nate Silver says, statistically, there has been more “*news*” in 2020 than in any election year since 1968.

Jon Stewart is back; he gave a long interview to The New York Times Magazine.

Matthew Yglesias wrote an important critique of Alex Vitale’s The End of Policing: it “left me convinced we still need policing.”

The New York Times published two more Condé Nast anti-glossy hatchet jobs: “A Reckoning at Condé Nast” and “Can Anna Wintour Survive the Social Justice Movement?”

Condé Nast’s head of video content has resigned over accusations of bias.

Faced with a lawsuit, a Fox News lawyer argued that viewers of Tucker Carlson Tonight don’t expect the show to report facts: “What we’re talking about here, it’s not the front page of The New York Times. It’s Tucker Carlson Tonight, which is a commentary show.”

CNN and others offered a first look at the “bombshells” in John Bolton’s new book, The Room Where It Happened; most notably, Bolton writes that Trump asked China’s Xi to help him get re-elected; the book is available for pre-order, and is #1 on Amazon; The New York Times already reviewed it.

Maggie Haberman on Trump’s “self-sabotage.”

“In denial”: Trump’s White House has continued to completely ignore COVID-19.

“Wednesday night massacre”: Trump appointee Michael Pack cleaned house at the US Agency for Global Media; The Washington Post has more context.

“The Bosses Are in Their Country Houses”: Ben Smith’s sinister column from last week.

Raising his voice on last Wednesday’s Morning Joe, Joe Scarborough condemned Facebook, Zuckerberg, and Sheryl Sandberg in a long monologue: “Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg are only interested in protecting their billions!”

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings donated $120 million to historically black colleges and universities and the United Negro College Fund (UNCF).

Hulu has started testing its own communal “virtual watch party” feature – dubbed Hulu Watch Party – to keep pace with Netflix’s own virtual watch feature, Netflix Party.

HBO has filmed a celebrity-filled comedy special called Coastal Elites, apparently about “characters from New York to Los Angeles coping with politics and the pandemic”; it will air in September.

Amazon has acquired the worldwide streaming rights to a forthcoming untitled Stacey Abrams/voting rights documentary, directed by Liz Garbus and Lisa Cortés.

Twitter launched “audio tweets.”

Bob Dylan released a new album.